Romantic (Early Victorian)

Contemporary Events

- In England, George IV’s reign ends in 1830. He is succeeded by William IV. William is followed by his niece Victoria in 1937. She was 18 upon her ascension. She rules England for the rest of the century, passing in 1901. She was a much loved and respected monarch, restoring faith to this style of government. The time of her reign is often referred to as “The Victorian Era”.

- Literature, music and graphic arts from 1820-1850 emphasized emotion, sentiment and feeling in reaction to the strict rules governing classical styles of the previous centuries. Nicknamed “Romantics”, these artists focused on content over form. They enjoyed breaking the rules. Romanticism was a rebellion against restricted artistic expression. They loved other times and places, dreaming of what life was like in the past and in exotic locales. The Romanesque-Gothic Era (Medieval) was a a favorite of Romantic artists. They invented the genre of historical fiction. Writers included Walter Scott, Alexander Dumas the Elder (Three Musketeers), Mary Godwin Shelley (Frankenstein), and Edgar Allen Poe, Lord Byron, John Keats.

- Westward expansion begins in the United States. Texas was annexed in 1845. Following war with Mexico, New Mexico and California were ceded to the US. The Oregon territory follows shortly behind.

- The Monroe Doctrine of 1823, gave notice to Europe that the American continent was no longer available for colonization.

Romantic-Women (~1820-1835)

Fashion Plate from The Royal Lady’s Magazine, September 1831

This fashion plate from the September 1831 issue of The Royal Lady’s Magazine demonstrates many of the the characteristic trends of the Romantic Era.

These include:

-a silhouette that is wide and top-heavy, especially when compared to the vertical columnal silhouette of the previous period.

–demi-gigot sleeves (full and balloon-like from shoulder to elbow and tight fitting elbow to wrist). Other popular large sleeve styles included the leg-of-mutton/gigot sleeve, the imbecile/idiot sleeve, and the Marie sleeve.

-a tiny, corsetted waist sitting a few inches above the natural waistline

-cone-shaped skirts created from gored (triangular shaped) panels. Hem widths gradually increase throughout the period. During the early years of the period fullness at the waist is minimal.

-Sleeves sit low on the shoulders and necklines are wide, baring the shoulders. Here the exposed neckline is concealed by decorated, coordinating pelerines (large removable collars) for proper day wear.

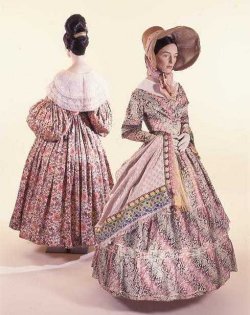

1835 day dress white cotton with pink, lavender and blue flower print, 1835 day dress in indian printed cotton of rasberry and blue flowers on white ground, 1837 summer morning dress in white checked muslin with leaf pattern, 1838 day dress in red wool gauze. Kyoto Collection

Romantic Era dresses were often described by either the time of day during which they were to be worn (ie. a morning or an evening dress) or the activity for which they were intended (ie. a promenade (walking) or a carriage dress). Very often the differences between the types of dresses is so subtle, it is difficult to distinguish the styles.

The following distinction can be made, however:

-Dresses for day wear are more conservative. They tended to have shorter hemlines, higher necklines, longer sleeves and were made of sturdy, sensible fabrics (ie. cotton and wool).

-Dresses for evening allowed more skin to show. They were generally floor length, have open exposed necklines, shorter sleeves, and were made of fancier fabrics (ie. satin, taffeta, moire).

All four of the dresses pictured above date between the years 1835 and 1838. All are considered to be day dresses. The three dresses on the left are made of cotton and the one on the right is made of wool gauze.

Hand colored fashion plate from The Royal Lady’s Magazine, June 1831

The June 1831 issue of The Royal Lady’s Magazine label the dresses pictured in this fashion plate as the following (from left to right):

-A Walking Dress

-An Evening Dress

-A Carriage Dress

-A Morning Dress

-A Carriage Dress

With the exception of the exposed neckline and shorter sleeves, for us (the modern students of fashion history) it is difficult to discern the difference between all of these different styles. However, women of the period could certainly tell the difference.

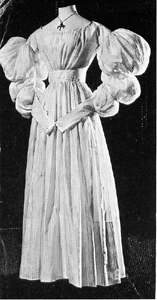

Extant cotton dress from the late 1830s with Marie sleeves.

Three variations of the dominant hat shape of the period are also shown in the plate above. Bonnet shapes were all the rage for Romantic women. There is evidence of both utiliatrian and decorative styles. Those shown here would be considered examples of the latter.

The muslin day dress pictured at the left features a style of sleeves known as the Marie sleeve. The sleeves are cut full and balloon-like from shoulder to wrist, much in the fashion of the imbecile/idiot sleeve. The fullness is then arranged and secured into graduated puffs along the length of the arm.

In the plate below, the evening dress at the far left has leg-o-mutton/gigot sleeves(cut full and balloon-like at the shoulder and tapering to the wrist).

Uncolored fashion plate from The Lady’s Magazine, April 1831

Romantic Period stays, petticoat, and sleeve support c.1830s. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Fischu style pelerine over a gigot sleeve day dress c. 1830, Memorial Hall Museum

Romantic Women (~1836-1850)

1840’s fashion plate hand colored.

Fashion plates tended to present an idealized image of current trends. As tight-lacing becomes the vogue in corsetry, waists were depicted as impossibly tiny. While a fashionable woman desired a 15-inch circumference at her mid-section, many more ladies claimed to have successfully achieved this feat than was true in reality. Nonetheless, this was the ideal of beauty for which women strived.

Never before had corsets been cinched tighter. Lacing holes formerly reinforced through stitching (in a manner reminiscent of a buttonhole), now are reinforced with steel eyelets. This is evidence that women were pulling harder on their laces and the resulting amount of flesh cinched became more drastic than ever before.

The tiny waist was also accentuated by increased fullness in the skirt. During the later years of the Romantic Era, fashionable dresses moved away from a cone-shaped skirt, the silhouette becoming more of a bell. This bell shape was supported by multiple layers of petticoats.

Janet Arnold. Patterns of Fashion. c.1837-41. Gloucester Museum.

During the later years of the Romantic Era, the puffed upper body silhouette takes on a deflated quality. This is particularly true in regard to the sleeve shapes. Much of the former fullness is still present in the cut, however it is now pushed downward. This drawing demonstrates one approach at achieving this. Decorative additions have been added to the upper sleeve, pushing the fullness below the elbow. If a woman was unable to purchase a new dress the sleeves could be creatively reworked in order to acheive this effect.

Other characteristics of the late Romantic Era pictured here include:

–a movement away from skirts constructed through triangular shaped gores towards those constructed using large rectangular panels pleated into the waist. Hem widths continue to increase as does the fullness at the waist, resulting in deep pleats and the aforementioned “bell” shape.

–back waistlines remain horizontal, but fall a few inches to align with the natural waistline. In the front, it becomes common to see a dipped waistline, reinforcing the idea of the silhouette being pulled downward.

Franz Xaver Winterhalter Marie Caroline de Bourbon, Princesse des Deux-Siciles, Duchesse d’Aumale, belle fille de Louis-Philippe 1846

Romantic Era women favored the hairstyle pictured here. A la Chinoise was a coiffure created by pulling the hair at the back and the side of the head up into a knot or bun while arranging hair at the forehead and temples into large sausage curls.

The deeply pleated waistline of the skirt and the dipping front waistline are also clearly depicted here. Notice that the upper body silhouette has drastically narrowed and the overall cut seems to point downward.

1850s fashion plate. Hand colored.

1845 Fashion Plate. Hand colored.

Transition of Romantic gown from 1830s to 1837. Museum of Costume. Quebec, Canada

Early photographic image of an 1840s couple.

Romantic Women-General

Both of these girls wear variations of the a la chinoise hairstyle.

Both of these girls wear variations of the a la chinoise hairstyle.

The girl at the left also wears a ferroniere (a jewel suspended from a ribbon and worn in the middle of the forehead). This is an imitation of a style from the Middle Ages. This Romantic fad is evidence of how literature influenced fashion. Romantic citizens often dreamed of other times and places–usually idealizing and “romanticizing” the past and foreign lands. The days of feudalism, knights, and princesses were among their favorites about which to fantasize.

Out of this preoccupation with the past, is born the genre of historical fiction. Romantic writers emphasized the maidens who died for love (almost always of “the consumption”) and vixens whose hard-heartedness tortured the heart of her lover. Romantic women devoured these novels and aspired to emulate their favorite swooning and captivating heroines.

As a result, illness became a fashion statement. Women cultivated a sickly paleness of complexion (often enhanced by rice powder). They lauded of their illinesses like trophies, often trying to out do one another with their laundry list of maladies. Due to extremely “tight-laced” corsets, the Romantic woman had no problem “swooning” like the best literary heroine.

French Fashion Plates 1840 to 1850

During the Romantic Era, the Male sphere and Female sphere became increasingly separated, especially among the upper classes. The home was no longer the center of business affairs, but now served as the center of entertainment. The Victorian woman–a subordinate of her husband–was expected to live a “doll-like” existence while playing hostess to her husband’s affairs.

A substantial wardrobe of clothing was necessary in order to fulfill this role effectively. Stylish gowns of the Romantic Era featured sleeves set low on the shoulder. Women could not raise their arms above their heads. This combined with an extremely tight-laced corset rendered a fashionable woman incapable of performing any physical labor. Servants carried out the physical housework, while the lady of the house busied herself with low physical activities such as sewing, embroidering, modeling in wax, sketching, painting on glass or china, and decorating other functional objects in the home.

Clothing of the period was still constructed by hand. The first sewing machine readily available for public purchase was invented by Elias Howe in 1846, but it did not become used extensively until after the Civil War. One of his machines could do the work of approximately 10 individual stitchers, thus forever changing the nature of the garment industry.

Romantic-Men (~1820-1850)

Men’s dressing coat..worn over a matching waistcoat 1830

An elegant man of the upper class could feasibly change his clothing 3-4 times a day. Like their female counterparts, male attire was often specific to the time of day or activity for which it was worn.

The gentleman pictured here is wearing attire that was considered undress, which consisted of a dressing gown/banyan and slippers. The stocking cap upon his head was also common. This was a typical ensemble for the relaxing hours of early the morning and late evening.

He would change at some point before the mid-day meal into one of his day/half dress styles. This generally consisted of a shirt, neckwear of some sort, a waistcoat, pantaloons/trousers, a coat/jacket and a hat.This ensemble generally consisted of coordinating fabrics, but often coat and pants were of different fabrics. The components were the same for full dress attire. The formality of this attire was found in the vogue for dark (usually black) matching coat and trousers. A white waistcoat and black or white neckwear was the most formal ensemble.

from “Journal des Dames,” May 1823.

The biggest clue signifying the Romantic Period in men’s wear is the illusion of the “nipped” in waist. This reflects the feminine “tight-lacing” trend. For the first time, tailors begin to add a complex inner structure to coat construction. This included internal padding–especially in the shoulder area. Broad shoulders coupled with trouser fullness at the waist helped to create a male “hour glass” silhouette. Many men even went so far as to wear corsets themselves. This is most common early in the period (~1820-1830)

The new tailoring processes not only changed the male silhouette, but set new standards for suit construction. Outwardly, the male wardrobe was growing more conservative and aesthetically boring. Inwardly, however, the construction was becoming more and more complicated. Quality of construction, rather than decoration, distinguished fashionable gentleman from the lower classes.

Tail coats and cutaways still remain the most popular coat styles. However, the frock coat (pictured here) is gaining popularity. This style is cut with a full, often gored, skirt and there generally is a seam at the waist (the seam cannot be seen in this particular picture). He has a high collared shirt (collar points come up to the chin) with a printed cravat around his neck. He has a smartly tailored waistcoat and is wearing striped pantaloons with an instep strap passing underneath the foot. Previously, pantaloons could be rather tight fitting. As we move further away from the last period (Empire/Directoire) fullness is gradually added at the waist (similar to what is happening in the skirts of the female wardrobe). However, the fullness continues to taper into the ankle–creating a “pegged” look. The instep strap is still a common feature.

During the Romantic Period the terms “trousers” and “pantaloons” are used interchangably.

Detail from a fashion plate c.1846

Top hats are the most common head covering for both half dress and full dress styles. They were most commonly made of beaver, bear, or silk (the latter being the most formal). A variation of the top hat was the gibus. Always a silk hat, this variation folded flat so that it could be carried under the arm. An internal spring allowed the hat to be snapped open–a dramatic and impressive gesture.

Fashion Plates from Le Folliet c.1840

A greater number of outerwear options become available for Romantic men. Pictured here are two outergarments (left & center) and a caped, double-breasted frock coat (right).

Outergarments added to the drama of an ensemble. Cloaks make a strong comeback. This is example of the a throwback to the styles of the Middle Ages–a true “romantic” trend. They appear most often in formal evening attire, and thus are most often depicted in dark colors (most frequently black). Satin details (ie. collars) are also very common.

The gentleman at the left is wearing a paletot–a short greatcoat with a small flat collar. These are seen in single and double breasted versions and may or may not also have lapels. This coat would be worn as a half dress style rather than full dress.

“Monsieur Leblanc,” by Ingres, 1823.

This gentleman wears a long outergarment thrown backwards on his shoulders. The garment appears to have a wide caped collar. It is impossible to tell from this drawing whether or not the garment has sleeves or is a large sweeping cape. If the garment is sleeved it would be considered a garrick (a boxy, large greatcoat with one or more caped collars over the shoulders). If it is a cloak it would be considered an inverness (a cloak with one or more caped collars over the shoulders, in later periods plaid versions with matching caps–a la Sherlock Holmes–become popular).

Notice the shape of his top hat and how it differs from those pictured above. The above hats are considered to be of the stove-pipe style, while the one pictured here is belled. Both styles are seen throughout the period.

Wiskonsan Enquirer (Madison, Wisconsin) Oct 20, 1842

“The Parting”, by Deyeria, c.1835 in Max von Boehn’s Modes and Manners of the 19th Century

http://www.costumes.org/pages/regentfashplates.htm

QUICK REVIEW

TYPE OF DRESS: Heavy tailoring returns for ladies. Both genders heavily tailored.

TEXTILES: Men maintain favor for wool suits. Silks return for ladies’s gowns though cotton gowns are still very common as well. Linen is common for shirts, chemises, and other layers close to the skin.

SILHOUETTE SHAPE: Hourglass for both genders. The hourglass will be of similar size above and below the waist (large bell like skirts paired with large sleeves). Waist placement will be 1-2″ above natural (approximately at the base of the rib cage).

BASIC GARMENTS: Men: 3-piece suit (frock coat, waistcoat, pantaloons) worn with a shirt and cravat OR stock & solitaire. Men appear “wasp waisted” due to the fit & flare of the frock coat and pleats appearing in the waist of the pantaloons and possible corseting. Women: Chemise, layers of petticoats, corset (tight lacing and body modifying), possible drawers, gowns with huge sleeves, slightly elevated waist, bateau necklines and ankle length bell shaped skirts, bonnets, fischus or pelerines to cover the neck and collarbone for daywear.

MOTIVATIONS FOR DRESS: Hygiene and Modesty. An attitude of coy prudery replaces the liberal attitudes of the neoclassical era.

KEY IDENTIFIERS: Men: frock coats, top hats, pegged trousers, Wasp waist “possible corset”, “M” or “W” lapels, fullness at top of coat sleeves. Women: tiny waist (tight laced corset reinforced with eyelets), bell shape skirts, huge sleeves, bonnets, ankle length skirts, wide bateau necklines covered with a wide collar or fischu for daytime.

Recent Comments